Community, Film, Meaning: Introducing Gaetano Kazuo Maida

By Ida Eva Zielinska

Published #61 | Summer 2021 Issue

Gaetano Kazuo Maida, Executive Director of the Buddhist Film Foundation and International Buddhist Film Festival. Photo: Bart Nagel

SHARE

Film producer and international film festival organizer Gaetano Kazuo Maida is Executive Director of the Buddhist Film Foundation/International Buddhist Film Festival. He was one of the founding directors of the quarterly Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, and was producer/director of Peace Is Every Step, a film profile of Vietnamese Zen teacher and activist Thich Nhat Hanh, narrated by British actor Ben Kingsley.

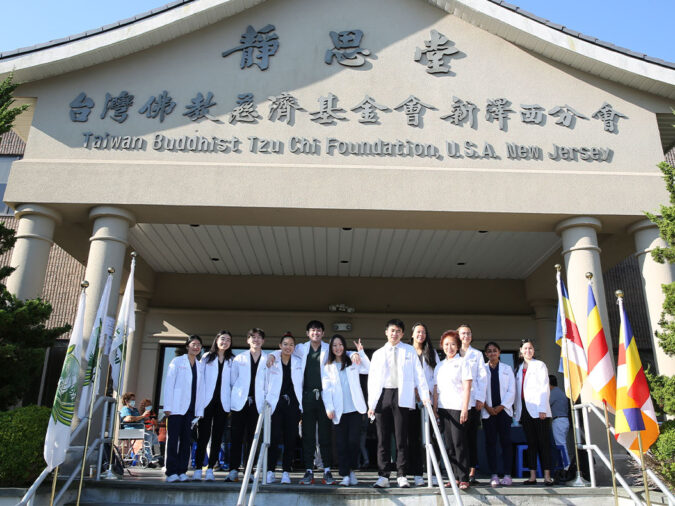

Tzu Chi USA’s film production team is honored that our documentary series On the Buddha’s Path will be on the International Buddhist Film Festival circuit in 2021. The entire series of seven films will screen in the BuddhaFest Online Festival from June 21 to August 15.* One of the films in the series, the feature documentary Karuna, about the humanitarian work of the non-profit Karuna-Shechen, co-founded by Buddhist monk Matthieu Ricard, will also screen at the International Buddhist Film Festival.

On this occasion, we’re thrilled that Gaetano has agreed to this interview touching on his work and the theme of this Summer Issue of Tzu Chi USA Journal, which centers around the question of what is a meaningful life.

Q: In your view, what constitutes a meaningful life?

I think it’s a truism that each individual makes the determination about what constitutes a meaningful life, so who am I to say? For me, for most of my life, meaning has come from feeling that I could be useful, of service to something or others beyond myself, even beyond family.

Q: Is this view evolving as you gain more perspective and life experience over time?

I’m old, and what comes with age is the realization that I know less and less as time goes on, that even the certainties of experience should be questioned. Perhaps most of what we think we “know” is habit, tradition, projection, attachment…

Q: What influence does Buddhist philosophy have on your perspective? When and how did a connection with the Buddha Dharma manifest in your life?

The first I heard of Buddha was when I was in my early teens, in a book by a Greek author, Nikos Kazantzakis, Zorba the Greek. In it, the author is remembering a period of his life spent with a notable character, the Zorba of the title, attempting to build a mining operation that the author had inherited but had no vocation for. He sat on the beach struggling with a book he was writing about the Buddha, while Zorba worked with the laborers. The two would gather at night over dinner by the sea and debate the way of the intellect vs. the way of the body, the senses (and don’t get Zorba started about the way of the monk!). Guess which won? (He also wrote an unproduced play entitled Buddha, set in civil war and flood ravaged China.) But as little as that book had to say about Buddhism, it was a hint, a clue, and I pursued it, first in other books, then by meeting teachers, first in California, then in New York.

Q: How did your work with Tricycle Magazine and the Buddhist Film Foundation /International Buddhist Film Festival begin?

A number of us who were later involved with the founding of Tricycle joined the gathering in Barnet, Vermont in 1987 for the cremation ceremonies for Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche. This unprecedented in the U.S. display of traditional rituals for that Tibet-born teacher who was so influential on Western practitioners, had a big effect on many. We sensed that this event perhaps marked the end of a chapter in the history of Buddhism here and we asked each other “what does this mean, what should be done?”

We each had an idea: one decided to do a book, one focused on a new edition of a previous book, one had an idea for an opera, I had been photographing at various Buddhist centers for several years and thought there might be a book in that, etc. When we all got back to NYC a handful of us started meeting regularly for pizza and conversation to share ideas and plans. It soon became apparent that the only way for us to really approach the next chapter of Buddhism in the U.S. was via a periodical, sharing an ongoing and evolving story, and we threw ourselves into making that happen. The first issue of Tricycle was published in June, 1991 (thirty years ago!), debuting at what was then called the American Booksellers Association (ABA) conference (now the BEA).

One of the pieces of the planned arena that we thought Tricycle could encompass was a Buddhist film festival. There were many other challenges for a young magazine of course, plus there were very few appropriate films of note then, so the film festival ended up on the back burner. I moved to California and headed up the west coast office for a few years, and because of my film work, ended up serving on the jury at the San Francisco International Film Festival. I got to learn the festival business from the inside after having toured the international festival circuit with the first film I’d been a producer on. So when Martin Scorsese’s Kundun came out in 1997, I was very prepared, and I suggested it was finally time. Tricycle told me they had more than enough on their plate though, and that I should pursue this independently. Thus Buddhist Film Foundation was born.

Q: How does your work with Tricycle and the Buddhist Film Foundation/International Buddhist Film Festival add meaning to your life?

It’s all of a piece. Both the magazine, in the 90s, and the festival, since 2000, allowed me to both explore the Buddhist arena with access, and to share with audiences compelling things I have found in one way or another. The next step for us is a video streaming platform to serve as an archive and a marketplace for this kind of cinema, buddhistfilmchannel.com, coming soon.

Q: You have also produced and directed documentary films yourself. What has been the most meaningful part of that journey?

Filmmaking is one of the tools I’ve been able to utilize over the years, but not everything, not every story, should be a film of course. So a decision to embrace the struggle of making a film is not taken lightly. [Recent surveys have confirmed that a majority of independent filmmakers here (those not in the employ of studios, broadcasters, or big production companies) are unable to support themselves through their films alone.] That said, once I’ve determined that an idea I’ve had or a story that has come to me can best (or only) be served by a film, there’s nothing quite like the energetic satisfaction of engaging with all the dynamics of filmmaking.

I currently have three projects in different stages of development, one of which is a long-gestating series (targeted for PBS) inspired and informed by the late Rick Fields’ book How the Swans Came to the Lake (fourth edition coming in August), entitled The American Story of Buddhism. The best part of this work is the collaborative spirit; it’s a rare film that is made by a single person, and I welcome the team building and creative efforts of everyone.

Q: At the root of Tzu Chi USA’s reasons for producing the On the Buddha’s Path series was to celebrate and inspire “compassion in action” since it is at the heart of the Buddhist Tzu Chi Foundation’s missions and activities.

Concurrently, we were looking to create connections between different Buddhist communities and traditions by presenting their approaches and activities on the path of compassionate social service.

And, having watched “Encounter with Gaetano Kazuo Maida,” the January 2021 episode of John DiLeva Halpern’s YouTube series, I see that building community and creating bridges is also important to you. I was touched by how you spoke about being a bridge between cultures just by your heritage, having Sicilian and Japanese parents. You also talked about being “born with a communitarian gene.”

Could you share more about that and how focusing on universal commonalities rather than divisions is vital in the world today, even for the survival of Buddhism? And, of course, does having this outlook add meaning to your life?

I grew up in the Bronx, New York, among a circle of progressive/activist families, almost all of which were mixed in some way (Japanese and Jewish, Sicilian and Japanese, African-American and Jewish, etc.) and in a mixed neighborhood (Sicilian, Puerto Rican, African-American, Jewish) so frankly, it was quite a shock when I got to high school, a long way from my neighborhood, to discover that not everyone had that experience of heterogeneous community, and I was the odd one out. My upbringing allowed me (required me?) to view the world as always potentially coming together in justice rather than fragmented in fear or division forever. The Buddhist traditions offer an open door to everyone, theoretically, with no caste, race, class, gender/orientation, or religious barriers. I have not found a better vehicle, or vocabulary, for my energies and attention.

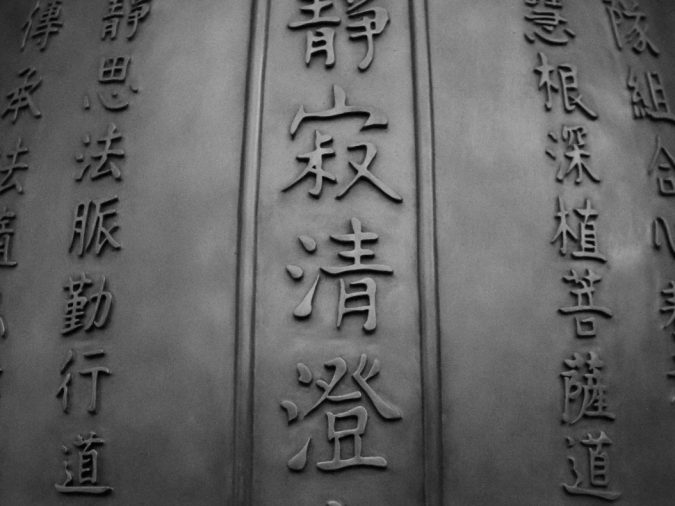

Q: Tzu Chi USA’s journal team also discovered that you have a passion for tea. Coincidentally, Tzu Chi produces different varieties of its signature Jing Si Tea, which is grown in Taiwan. Sales of the tea support the Jing Si Abode in Hualien, the spiritual home of all Tzu Chi volunteers and where Tzu Chi’s founder, Dharma Master Cheng Yen, resides alongside her monastic disciples.

What most fascinates you about tea, its origins and history, rituals, relationship to meditation and Buddhism, and so on? How does tea relate to building community, finding meaning, and more?

This question deserves a book (or a film!)… Briefly: even though I had a Japanese mother who made genmaicha (roasted rice and green tea) with fresh ginger for me if I ever had a cold, I really knew nothing of tea, of its history, of its incredible variety, and its delights, until I fell ill in my early 30s and was told to give up my habit of making and inhaling multiple double espressos daily. I asked that naturopath what I could drink instead, and he said, “you’re half-Japanese, you should drink green tea.” In those days (early ‘80s) there was still little here besides cheap tins from China or Japan, and after a few months I said, “nothing this boring could have lasted three thousand years!” and decided I had to go to Asia and see for myself.

My first opportunity was my honeymoon in Japan with my wife, and after a round of astonishing tastings in Kyoto I realized they simply keep all the good stuff for themselves! The tea server then casually said, “you know, all tea originally comes from China,” which aroused my curiosity, and my next trip was to Taiwan where I dove deep into the tea world there and found my life’s other calling. The knowledge that all tea – white, green, oolong, black (hong, or red), and puerh – come from the same plant, the camellia sinensis, was a revelation to me at that time. Besides going back to Japan and Taiwan several times, I’ve also been to China, Korea, Singapore, and Hong Kong exploring tea, and of course since the advent of the internet, excellent teas are now available garden-direct and fresh from most producing nations. Plus there’s a whole new generation of serious tea houses in major cities like New York, Washington, San Francisco/Berkeley, Seattle, Vancouver, Boulder, Paris, and even London.

Both Buddhism and tea suggest a path to awakened mind, and it’s certainly no coincidence that tea and Buddhism co-evolved in China, Korea, and Japan. Several traditions of ceremonies/practices that focus on tea emerged from monasteries and now have schools of their own. (No offence to India, where Buddhism began, but tea was first cultivated there only in the mid-1800s, by the British, who used what we would now call intellectual property theft to bring tea seeds, plants, and workers from China to Assam and Darjeeling.) But tea is now truly universal, more consumed than any other beverage except water, and at the center of social life all over the world, despite the commercial successes of colas and coffee. (A sort of introduction to my view of the tea world can be had in Issue 71 of Kyoto Journal, which I guest edited a few years ago.)

If there’s one thing to take away about tea, it’s that you’ll never live long enough to try all the varieties, which is also to say there are as many tea traditions as there are teas in the world, so there’s no one “tea,” just many teas and styles. I favor the Taiwanese approach, especially the gao shan cha (high mountain tea), which requires and rewards an attentive practice (not unlike the Japanese chanoyu, but without the obsessiveness), but even there things are changing due to climate, political, environmental, and labor considerations, not to mention rising prices, so who knows? (Other Taiwan teas like baihao, baochong, tungting, and their hong cha are wonderful as well, and less expensive!)

For tea, the issues of worker justice, environmental concerns, standardized nomenclature, and supply chain transparency are all more important and urgent than the latest refinements of style and ceremony. All of the tea world’s constituencies, from farmers and producers to traders and retailers, to consumers and aficionados, will in the coming years, find it essential to embrace their common needs and aspirations with attention to those issues.

Q: If there’s something else that you’d like to touch on and share with our readers, please do.

One thing we keep in mind here is that Buddhist cinema is even at best just the “finger pointing at the moon,” and not a substitute for study and practice… you know, the path! And while we’re always hopeful of offering inspiration, we do not see ourselves as Dharma teachers, just friends tending the same garden.

One thing we keep in mind here is that Buddhist cinema is even at best just the “finger pointing at the moon,” and not a substitute for study and practice… you know, the path! And while we’re always hopeful of offering inspiration, we do not see ourselves as Dharma teachers, just friends tending the same garden.

Thank you, Gaetano.

Our whole team looks forward to when it, once again, becomes possible to meet in person freely. Then, we could gather to discuss life and meaning over a cup of tea!